Blog

Inside Claude Cowork: How Anthropic Runs Claude Code in a Local VM on Your Mac

Claude Cowork is a feature of the Claude Desktop app that allows Claude to execute code, manipulate files, and perform complex tasks autonomously. This post documents a deep investigation into how it works under the hood, covering the architecture, security layers, and interesting implementation details.

TL;DR

Claude Cowork runs a full Linux virtual machine locally using native virtualization. Inside this VM, it executes Claude Code CLI within a multi-layered sandbox. Network access is restricted to a strict allowlist, and MCP servers from Claude Desktop are dynamically passed through to the VM. Multiple conversations share a single VM instance, but each gets its own isolated session.

Contents

- TL;DR

- Introduction

- Architecture

- Isolation

- File Sharing

- Networking

- MCP

- Pre-installed Tools

- Security Implications

- Conclusion

Introduction

When you start a Cowork session in Claude Desktop, Claude can suddenly run Python scripts, process videos with ffmpeg, create PowerPoint presentations, and more. But how does it actually work? Is it a Docker container? A remote server?

Cowork is currently only available on macOS, so this investigation was conducted on that platform from both sides: from within the execution environment (Claude’s perspective) and from the host system (the user’s perspective), using Claude Code 1.1.799 (2e02b6). The findings reveal a thoughtful and robust architecture.

Architecture

The core architecture consists of three main layers:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ macOS Host │

│ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Claude.app (Electron) │ │

│ │ ├── UI Renderer │ │

│ │ ├── MCP Servers (Slack, Atlassian, etc.) │ │

│ │ ├── Network Proxy Service │ │

│ │ └── Virtualization.framework │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ stdio VirtioFS MCP SDK HTTP/SOCKS │ │

│ │ pipes mounts protocol proxy │ │

│ └──────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Ubuntu 22.04 VM (ARM64) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ /sessions/<name>/mnt/ ◄── VirtioFS ──► ~/<shared-folder>/ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ ┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ bubblewrap sandbox + seccomp (per session) │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ Claude Code CLI v2.1.15 │ │ │

│ │ │ --model claude-opus-4-5-20251101 │ │ │

│ │ │ --mcp-config {...} │ │ │

│ │ │ --allowedTools Task,Bash,Grep,... │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Network: :3128 (HTTP) / :1080 (SOCKS) → Allowlist │ │

│ │ Disks: rootfs.img (10GB) + sessiondata.img (36MB) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Claude Cowork is not a separate model, it is Claude Code CLI running inside the VM, orchestrated by Claude Desktop:

| Component | Value |

|---|---|

| CLI Binary | /usr/local/bin/claude (ELF 64-bit ARM aarch64) |

| CLI Version | 2.1.15 (Claude Code) |

| Model | claude-opus-4-5-20251101 |

| I/O Format | stream-json (bidirectional) |

| Session Resume | --resume <session-uuid> |

The CLI is launched with the following arguments:

/usr/local/bin/claude \

--output-format stream-json \

--input-format stream-json \

--model claude-opus-4-5-20251101 \

--resume <session-uuid> \

--allowedTools Task,Bash,Glob,Grep,Read,Edit,Write,... \

--mcp-config '{"mcpServers": {...}}' \

--permission-mode default \

--plugin-dir /sessions/<name>/mnt/.skills

Isolation

Virtual Machine

The execution environment is a complete Ubuntu 22.04 LTS virtual machine running on ARM64 architecture:

PRETTY_NAME="Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS"

Linux claude 6.8.0-90-generic aarch64 GNU/Linux

This is not a Docker container or a lightweight sandbox, it is a full VM with its own kernel, managed by Apple’s Virtualization Framework. The VM runs via com.apple.Virtualization.VirtualMachine, the same technology used by tools like UTM and Tart.

Resources allocated:

- 4 vCPUs (ARM64)

- 3.8 GB RAM

- ~10 GB virtual disk (sparse)

VM Bundle Structure

The VM files are stored locally at:

~/Library/Application Support/Claude/vm_bundles/claudevm.bundle/

| File | Size | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

rootfs.img |

10 GB | Ubuntu root filesystem (sparse) |

sessiondata.img |

36 MB | Persistent session data (/sessions) |

efivars.fd |

128 KB | UEFI boot variables |

macAddress |

17 B | Virtual MAC address |

machineIdentifier |

70 B | Unique VM identifier |

.rootfs.img.origin |

40 B | SHA1 hash for image verification |

The rootfs.img is a sparse file, meaning it does not actually consume 10 GB on disk, only the space needed for actual data.

Security Layers

The VM employs multiple security layers:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ macOS Host │

│ └── Apple Virtualization Framework │

│ └── Ubuntu 22.04 VM │

│ └── bubblewrap sandbox │

│ └── seccomp filter │

│ └── Claude Code │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

- VM isolation: Full hardware-level separation

- bubblewrap (bwrap): Linux sandboxing tool

- seccomp: System call filtering

- Network isolation: Traffic routed through local proxy (ports 3128/1080)

Multi-Session Architecture

A single VM instance serves multiple Cowork conversations simultaneously. Each conversation gets its own isolated session:

/sessions/

├── intelligent-loving-darwin/ ← Chat session 1

├── dreamy-optimistic-babbage/ ← Chat session 2

└── ...

Session names are randomly generated using a Docker-container-like pattern: adjective-adjective-scientist.

| Resource | Shared? | Notes |

|---|---|---|

/tmp/ |

Yes | Sessions can see each other’s temporary files |

/sessions/<name>/ |

No | Permissions drwxr-x--- block cross-session access |

| User (UID) | No | Each active session has its own Linux user (e.g., uid=1002) |

| Kernel/Processes | Yes | Same VM, same kernel |

| Network proxy | Yes | Same allowlist rules |

This was verified by creating a file in /tmp/ from one session and successfully reading it from another, while attempting ls /sessions/dreamy-optimistic-babbage/ returned Permission denied.

Interestingly, inactive sessions show nobody:nogroup as owner, while the active session has its own dedicated user. This suggests sessions are “depersonalized” when closed.

File Sharing

User folders are shared between macOS and the VM using VirtioFS, Apple’s high-performance paravirtualized filesystem:

/mnt/.virtiofs-root/shared/Downloads → /sessions/.../mnt/Downloads

This enables bidirectional file access: Claude can read and write to the user’s selected folder, and changes appear instantly on both sides.

Path Translation

Claude Desktop performs smart path translation in the UI. When Claude executes:

cp report.pdf /sessions/intelligent-loving-darwin/mnt/Downloads/

The user sees:

cp report.pdf ~/Downloads/

This translation is context-aware: it only rewrites paths that are actual file arguments, not string literals in other commands.

Networking

Allowlist

All network traffic from the VM is routed through a local proxy with a strict allowlist. Direct DNS lookups are blocked (socket(): Operation not permitted).

Allowed domains:

| Domain | Status | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

api.anthropic.com |

200 | Anthropic API |

pypi.org |

200 | Python packages |

registry.npmjs.org |

200 | Node packages |

Blocked domains:

| Domain | Response |

|---|---|

google.com |

403 Forbidden - blocked-by-allowlist |

api.github.com |

403 Forbidden - blocked-by-allowlist |

| Any other domain | 403 Forbidden - blocked-by-allowlist |

This means Claude can install dependencies via pip and npm, but cannot make arbitrary HTTP requests from the VM—curl to non-allowlisted domains is blocked, and the same applies to the WebFetch tool. However, WebSearch works as it uses the Anthropic API endpoint.

Host-VM Communication

Communication between Claude Desktop (macOS) and Claude Code (VM) uses multiple channels:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ macOS (Claude Desktop) │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ Electron App │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ stdio pipes ───┼──────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ Unix sockets ──┼───┐ │ │

│ └─────────────────┘ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

└──────────────────────────│──────────────────│───────────────────┘

│ virtiofs mount │ pipes

┌──────────────────────────│──────────────────│───────────────────┐

│ VM │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ /tmp/claude-http-*.sock pipe:[xxxxx] (stdin) │

│ /tmp/claude-socks-*.sock pipe:[xxxxx] (stdout) │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ socat → localhost:3128 Claude Code CLI │

│ socat → localhost:1080 --input-format stream-json │

│ (HTTP/SOCKS proxy) --output-format stream-json │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

| Channel | Mechanism | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Messages | Unix pipes (stdin/stdout) | JSON stream for user messages and responses |

| HTTP Proxy | Unix socket → socat → :3128 |

HTTP requests (pip, npm, API calls) |

| SOCKS Proxy | Unix socket → socat → :1080 |

Other network protocols |

| MCP | SDK protocol via pipes | Communication with MCP servers on host |

| Files | VirtioFS mount | Shared folder access |

The Unix sockets (/tmp/claude-*.sock) are mounted from macOS into the VM via VirtioFS, allowing socat processes inside the VM to bridge network traffic to the host’s proxy.

MCP

One of the most interesting aspects of the architecture is how MCP (Model Context Protocol) servers are integrated. Claude Desktop’s MCP servers are passed to the VM and made available to Claude Code. The MCP configuration is injected via command-line argument:

{

"mcpServers": {

"ea93ae0e-73b4-4d43-9bb0-2c3720b9d627": {"type": "sdk", "name": "..."},

"4b26c136-8d30-4046-b6ad-2e41dde789ea": {"type": "sdk", "name": "..."},

"Claude in Chrome": {"type": "sdk", "name": "Claude in Chrome"},

"My Custom Server": {"type": "sdk", "name": "My Custom Server"},

"cowork": {"type": "sdk", "name": "cowork"}

}

}

Official Anthropic integrations use UUIDs as identifiers (e.g., ea93ae0e-... for Atlassian, 4b26c136-... for Slack), while third-party and custom servers use human-readable names. The cowork server is built-in and provides tools like request_cowork_directory and allow_cowork_file_delete.

MCP servers configured in Claude Desktop are dynamically passed through to the VM. When a new MCP server is added to Claude Desktop, it becomes available to Cowork sessions. MCP servers use "type": "sdk" which means they communicate through the Claude SDK rather than stdio pipes, enabling Claude inside the VM to interact with applications running on the host.

Pre-installed Tools

The VM comes with a comprehensive toolkit:

Languages:

| Language | Version |

|---|---|

| Python | 3.10.12 |

| Node.js | 22.22.0 |

| Ruby | 3.0.2 |

| TypeScript | 5.9.3 |

CLI Tools:

ffmpeg/ffprobe4.4.2 — Video/audio processinggit2.34.1 — Version controlpandoc2.9.2 — Document conversionImageMagick6.9.11 — Image manipulationripgrep— Fast searchjq1.6 — JSON processingsqlite3— Database

Node.js Packages:

docx— Word document creationpptxgenjs— PowerPoint generationpdf-lib— PDF manipulationsharp— Image processing

Python Packages:

beautifulsoup4— Web scrapingcamelot-py— PDF table extractionpandas,numpy,matplotlib— Data analysis

Security Implications

The architecture provides strong isolation:

- No direct host access: Claude cannot access arbitrary files on macOS, only the explicitly shared folder

- Network allowlist: Only package registries (pypi, npm) and Anthropic’s API are accessible; arbitrary web requests are blocked

- Syscall restrictions: seccomp limits what system calls can be made

- Per-session sandboxing: Each conversation runs in its own bubblewrap sandbox with a dedicated user

- DNS blocked: Direct DNS lookups fail; all traffic must go through the proxy

Potential concerns:

- Sessions sharing

/tmp/could theoretically leak information between conversations - The VM persists between sessions, so artifacts may remain in shared spaces

This is a significant improvement over running code directly on the host or in a simple container.

Conclusion

Claude Cowork represents a thoughtful approach to enabling AI code execution. By running a full Linux VM with multiple security layers, Anthropic has created an environment that is both powerful (full Ubuntu with extensive tooling) and isolated (VM + sandbox + seccomp + network allowlist).

Key architectural decisions:

- Claude Code as the engine: Cowork is Claude Code CLI running inside a sandboxed VM, not a separate product

- Single VM, multiple sessions: Efficient resource usage while maintaining per-session isolation

- Apple Virtualization Framework: Native ARM64 performance on Apple Silicon

- VirtioFS: Fast, bidirectional file sharing with the host

- MCP passthrough: Desktop MCP servers are dynamically shared with the VM via SDK protocol

- Network allowlist: Permits dependency installation while blocking arbitrary web access

- Smart path translation: Seamless UX by rewriting VM paths to host paths in the UI

This architecture allows Claude to perform complex tasks—video processing, document generation, data analysis—while maintaining strong security boundaries. It is a practical solution to the challenge of giving AI systems the ability to execute code safely.

CVE-2024-40801: How a Sandboxed Mac App Could Steal Your Private Data Bypassing TCC Protections

This post includes the details of the first vulnerability I have ever reported to Apple. It was fixed on macOS Sonoma 14.7 and macOS Sequoia 15.0 as CVE-2024-40801.

TL;DR

A vulnerability in macOS allowed a sandboxed app to bypass TCC (Transparency, Consent and Control) protections and access sensitive user data without requiring user permission. By leveraging the container-migration.plist feature, a sandboxed app could request the migration of TCC-protected files (like Safari history, Mail database, or user documents) to its app container, effectively bypassing TCC and giving the app full access to these files. There are multiple examples included in this repository demonstrating the exploit.

Initial Report

Below is the full report as submitted to Apple. You can also check the GitHub repository that includes the example projects to reproduce the vulnerability.

Introduction

A sandboxed Mac app can exploit the container-migration.plist feature to get access to TCC-protected files without any user permission prompt.

For example, you can request the Safari history file or Mail database to be migrated by the App Sandbox to the app container, and it will happily do it. Once the files are in the app container, the app has full control to read and exfiltrate this data.

You can use the attached project to reproduce the exploit (check the demo video at Extra/Videos/ContainerMigrationExploit.mp4):

Steps to Reproduce

- Run the script at

Scripts/ContainerMigrationExploitReset.shin a Terminal with Full Disk Access. This script will:- Reset the App Sandbox container of the

Exploitapp (if it exists). - Reset the TCC permissions of the

Expectedapp that shows the proper expected behavior when accessing the protected files. - Create a demo file in the user Documents folder named

my-secret.txt. - Restore & back up the Safari history database (

History.db) and Mail recent searches plist (recentSearches.plist). Both of these files are protected by TCC, and reading them requires Full Disk Access as they contain very sensitive data like contacts and the browsing history. The first time the script runs, the restore will fail, but you can ignore it.

- Reset the App Sandbox container of the

- Open the Xcode project at

Projects/ContainerMigrationExploit.xcodeproj. - Run the

Expectedscheme: this is an un-sandboxed app that tries to read directly the files that the exploit app will steal. As you see, it triggers the expected TCC permission prompt when reading themy-secret.txtfile in the Documents folder, and it also cannot access the Safari history database nor the Mail recent searches plist as they are stored in protected directories. - Now run the

Exploitscheme: this sandboxed app is able to read the three files without any issue as they have been migrated by the App Sandbox into the app container.

Expected Results

As demonstrated by the Expected scheme, the app should not be able to access any of the data in the protected directories without user permissions and/or Full Disk Access. Even worse, a sandboxed app is able to get more access to sensitive files than an un-sandboxed app using this technique.

Actual Results

The Exploit app can access sensitive files protected by TCC without any user permission. This same technique can be used to exfiltrate the following data from a fully sandboxed app:

- User documents stored in the Documents folder (without any TCC prompt).

- Sensitive files in the Library folder:

- Safari history & bookmarks.

- Full Mail database & contacts.

- Other apps’ containers’ data.

- …

Annex I

This new version of the project includes a new Mail-app-specific example project in Projects/MailContactsExploit.xcodeproj that demonstrates how you can use this exploit to dump all your Mail contact addresses without any TCC prompt from a fully sandboxed app (demo video at Extra/Videos/MailContactsExploit.mp4).

This same exploit can also be used for a denial-of-service / ransomware attack as the original files (in this example, the Mail database) are deleted by the App Sandbox migration from the original location and are now in full control of the attacker app.

Annex II

Some details about how the exploit seems to work under-the-hood:

- The sandboxed app initializes the App Sandbox and connects to the

secinitddaemon. secinitdreads thecontainer-migration.plistfile in the app bundle.- As

secinitdhas thekTCCServiceSystemPolicyAllFilesvalue in thecom.apple.private.tcc.allowentitlement, it can access any protected directory and moves the protected files into the app container.

You can check the related Endpoint Security events from eslogger in the directory Data/EndpointSecurity/.

Annex III

This final version of the project includes a demonstration that this same exploit can also be used to exfiltrate both Calendar & Contacts databases, even though their paths are symlinked inside the app container, by leveraging a custom destination in the container-migration.plist file:

<dict>

<key>Move</key>

<array>

<array>

<string>${Home}/Library/Calendars/Calendar.sqlitedb</string>

<string>${Home}/Calendar.sqlitedb</string>

</array>

</array>

</dict>

You can check a Calendar-specific example project at Projects/CalendarExploit.xcodeproj and a demo video at Extra/Videos/CalendarExploit.mp4.

ChatGPT for Mac was storing all conversations in an unprotected location

This is a recap of some posts I published on Threads during the past week.

TL;DR

The OpenAI ChatGPT for Mac app stored user conversations in plain text in a non-protected location, making them accessible to any running app or malware. After public disclosure, OpenAI released an update encrypting the conversations but did not implement sandboxing.

Introduction

The OpenAI ChatGPT app on macOS is not sandboxed and stored all conversations in plain text in a non-protected location:

~/Library/Application Support/com.openai.chat/conversations-{uuid}/

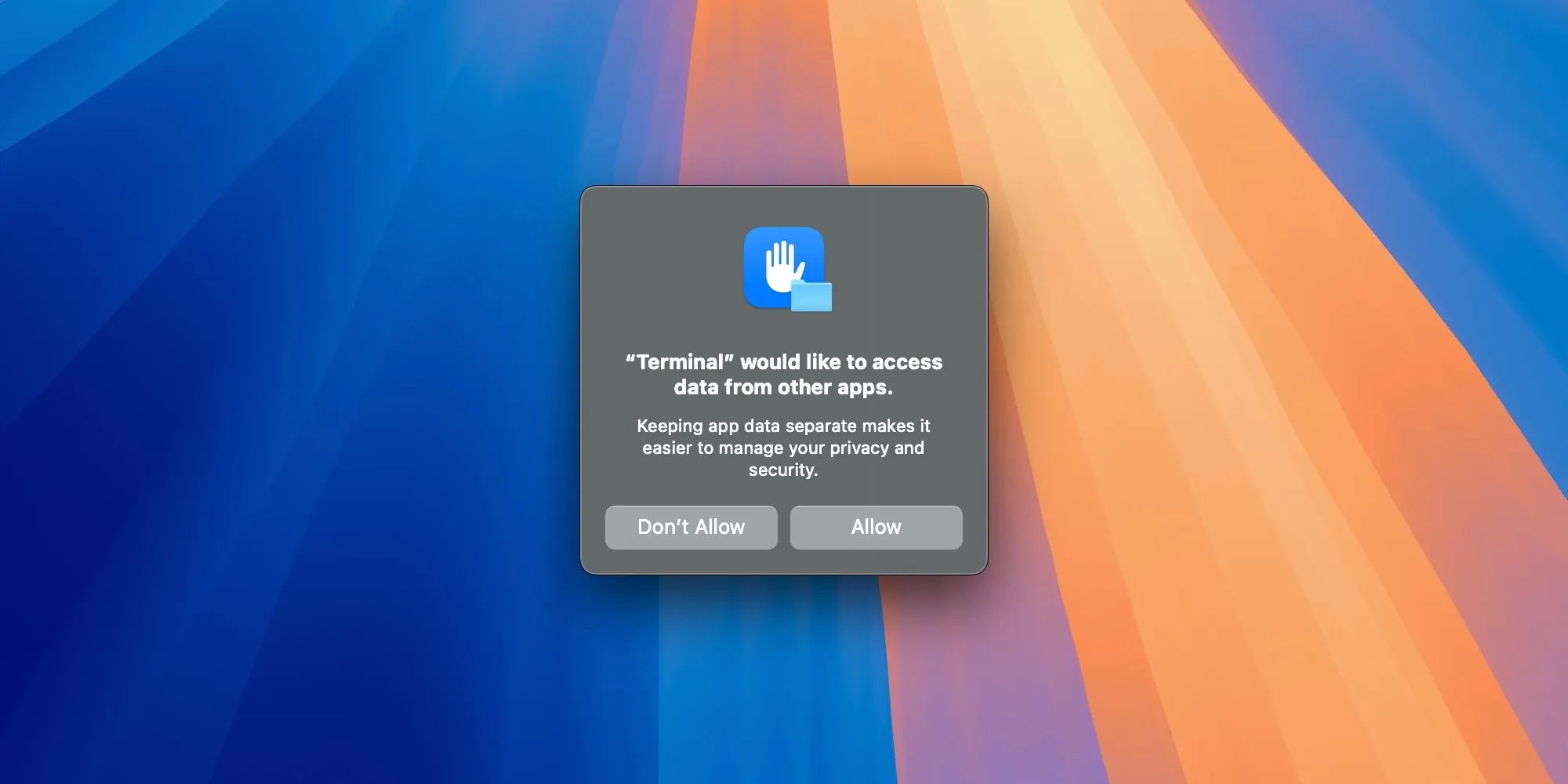

This approach is somewhat typical for non-sandboxed apps on macOS, but a high-profile chat app like ChatGPT should be more careful with user data. For example, Apple started blocking access to user private data 6 years ago with the introduction of macOS 10.14 Mojave. Before that, any non-sandboxed app could access any user file. With macOS Mojave, Apple began requiring explicit user permission to access sensitive files like the Calendar, Contacts, Mail or Messages databases. Later, Apple extended this requirement to the Desktop and Documents directories, and with macOS 14 Sonoma, any file stored by a sandboxed third-party app in its sandbox container is automatically protected. This protection prevents malware or untrusted apps from exfiltrating user data without triggering a permission prompt like this:

Unfortunately, OpenAI opted out of sandboxing the ChatGPT app on macOS and stored conversations in plain text in a non-protected location, disabling all these built-in defenses. This meant that any running app, process, or malware could read all your ChatGPT conversations without any permission prompt.

Example

Here you can see how easily any other app could access any ChatGPT conversation without any permission prompt:

You can check the source code of this demo app, ChatGPTStealer, on GitHub.

Aftermath

Initially, I reported this issue to OpenAI through their security bug reporting program in BugCrowd, but they marked the report as “Not Applicable” as “in-order for an attacker to leverage this, they would need physical access to the victim’s device.”

As I disagreed with that consideration, I decided to post this issue publicly on Threads & Mastodon to raise awareness and encourage OpenAI to fix this issue and hopefully sandbox the ChatGPT app on macOS. These posts gained attention and were eventually covered by The Verge, Ars Technica, 9to5Mac, and others.

Following these publications, OpenAI finally acknowledged the issue and released ChatGPT 1.2024.171 for Mac, which now encrypts the conversations. The conversations are now stored in a new location:

~/Library/Application Support/com.openai.chat/conversations-v2-{uuid}/

These files are now encrypted with a key named com.openai.chat.conversations_v2_cache stored securely in the macOS Keychain and the old plain-text conversations are removed after upgrading to the new version. However, the app is still not sandboxed, so the conversations are still stored in a non-protected location, but now at least they are encrypted so other apps can’t read them without user-granted access to the Keychain key.

Interestingly, macOS Sequoia will introduce protections for Group Containers, so non-sandboxed apps like ChatGPT could improve their security by moving sensitive data to a Group Container directory. This way, any other process or app trying to access the data would be blocked by the system, and a permission prompt would be presented to the user.

Creating Apple Wallet Passes Instantly With ChatGPT and MakePass AI

TL;DR

You can use the MakePass AI service in the MakePass app with the Ultra subscription to create Apple Wallet passes instantly using an input photo or document of a ticket or card:

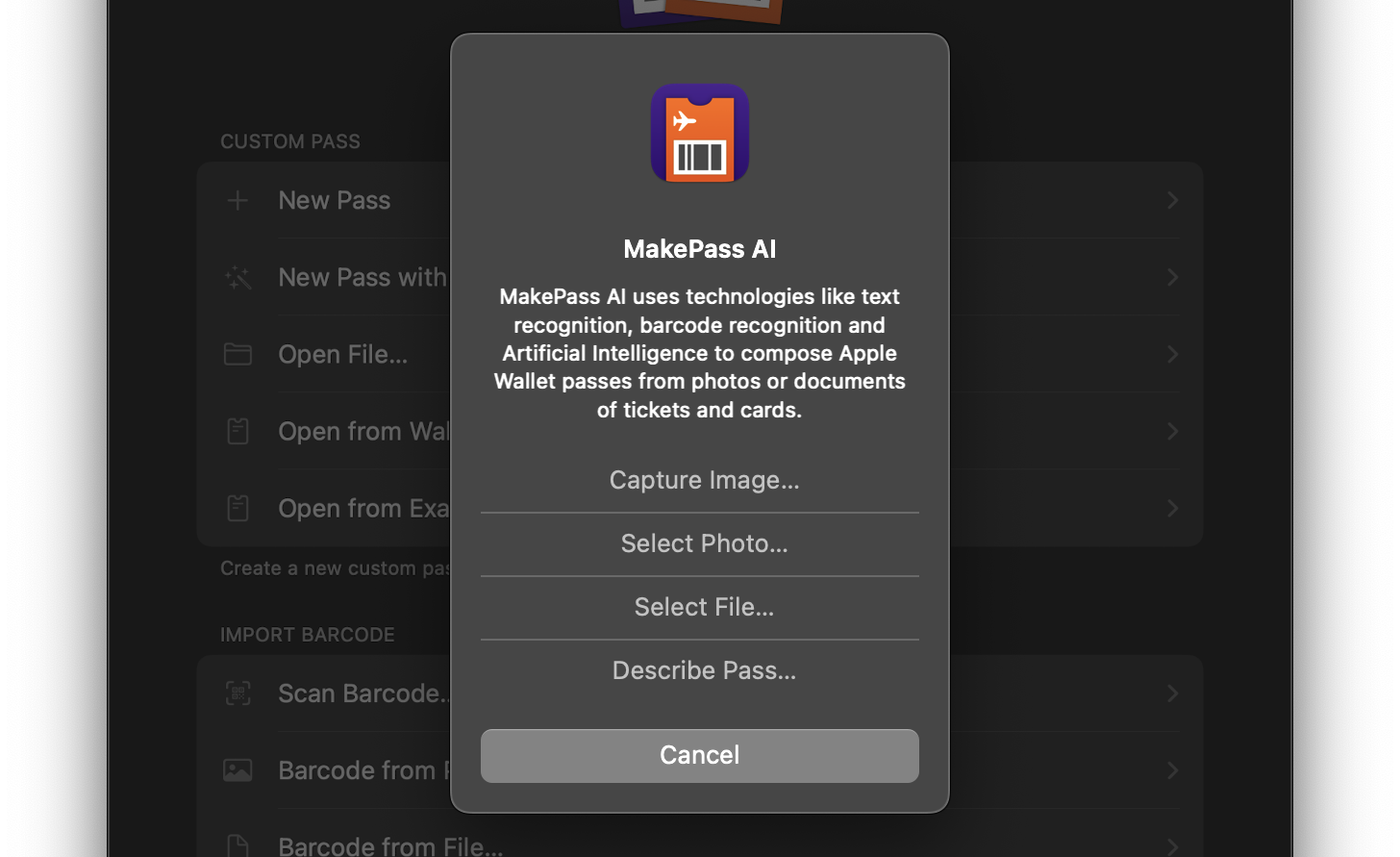

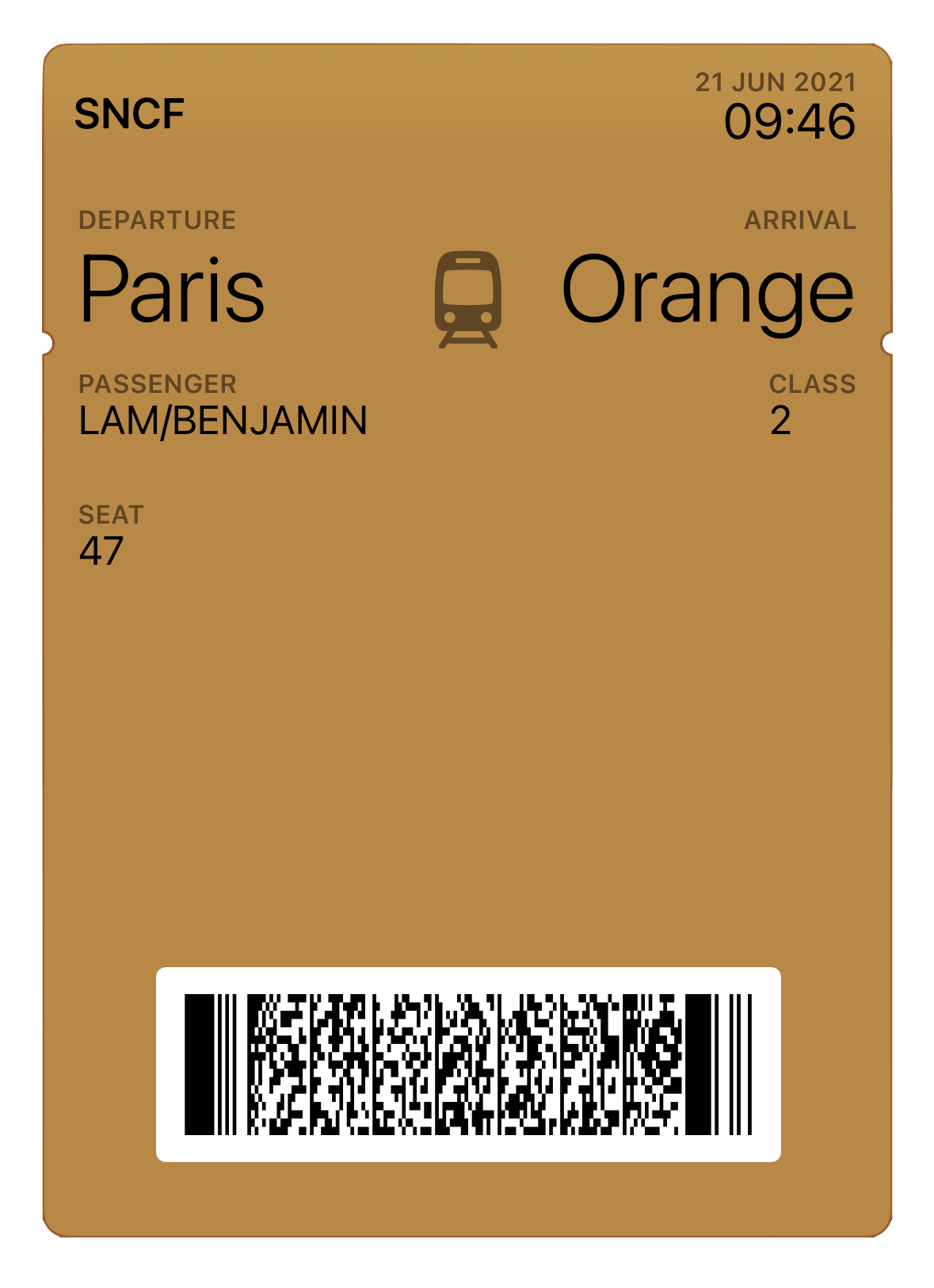

Introduction to MakePass AI

MakePass is a mighty Apple Wallet pass editor, with it you can create and customize a myriad of passes with complex layouts including images, barcodes, colors and text fields. Now it includes a new service called MakePass AI available with the MakePass Ultra subscription that allows you to create Apple Wallet passes instantly using an input photo or document of a ticket or card. It can even design the pass using a pass description.

MakePass AI uses technologies like text recognition, barcode recognition and Artificial Intelligence powered by OpenAI ChatGPT models to compose Apple Wallet passes from photos or documents of tickets and cards.

Examples

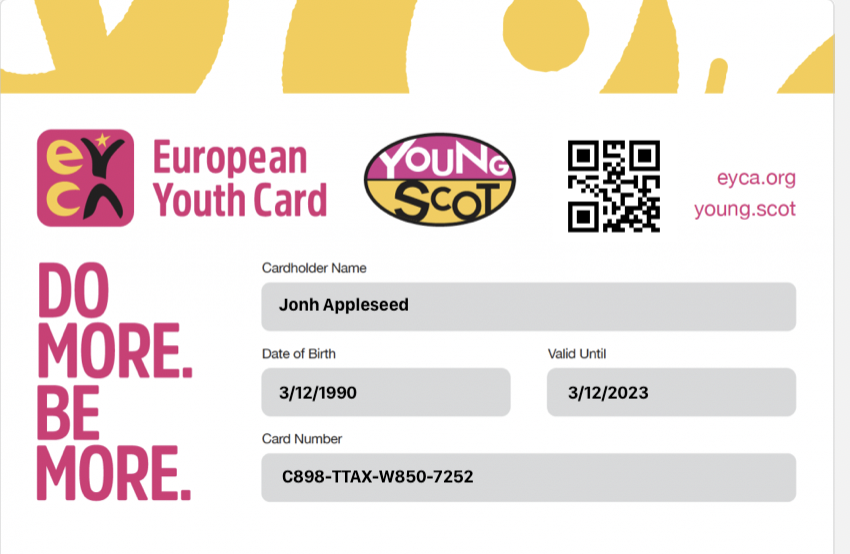

Here you can see some examples of passes generated automatically with MakePass AI from some input image or document:

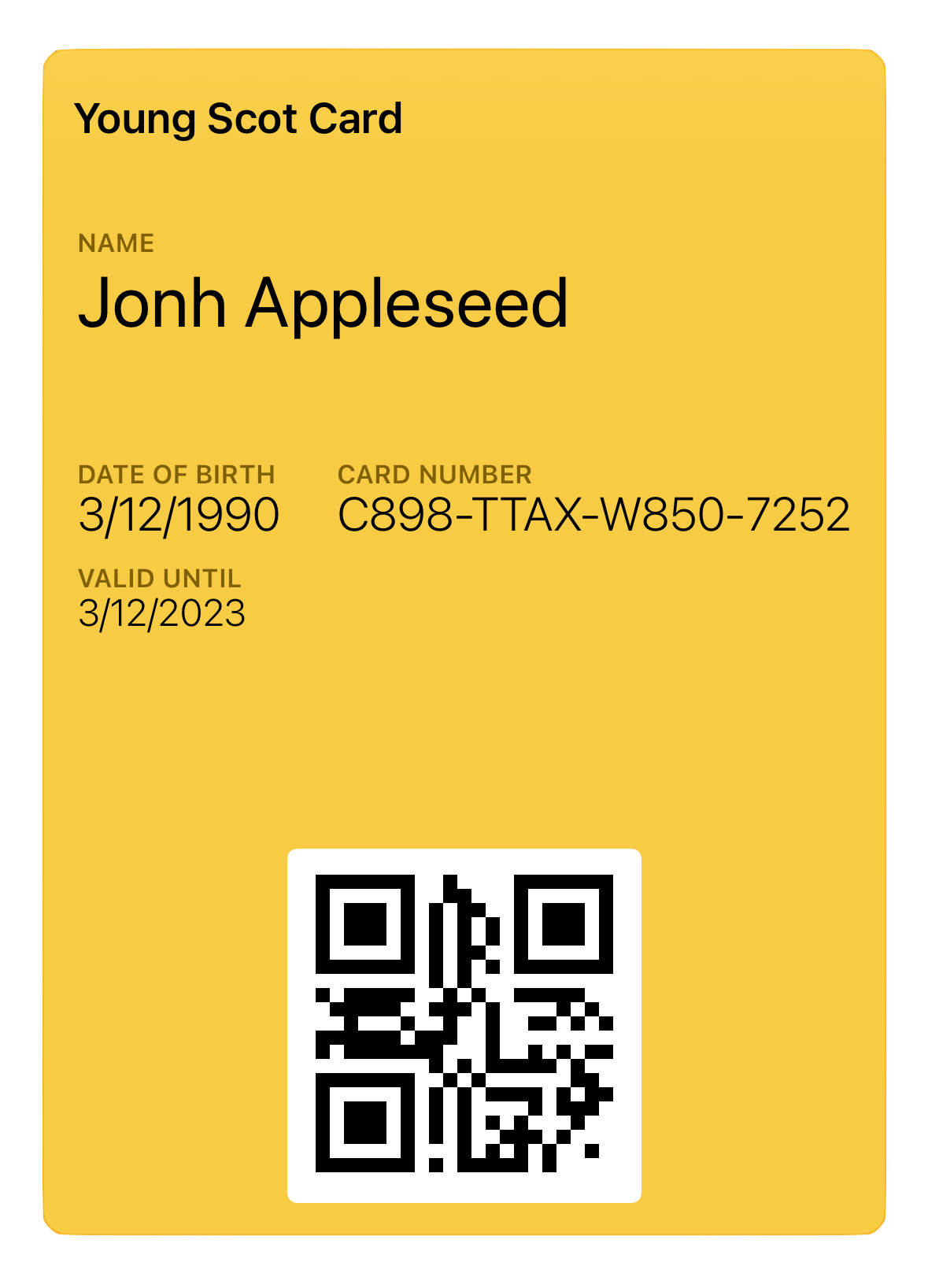

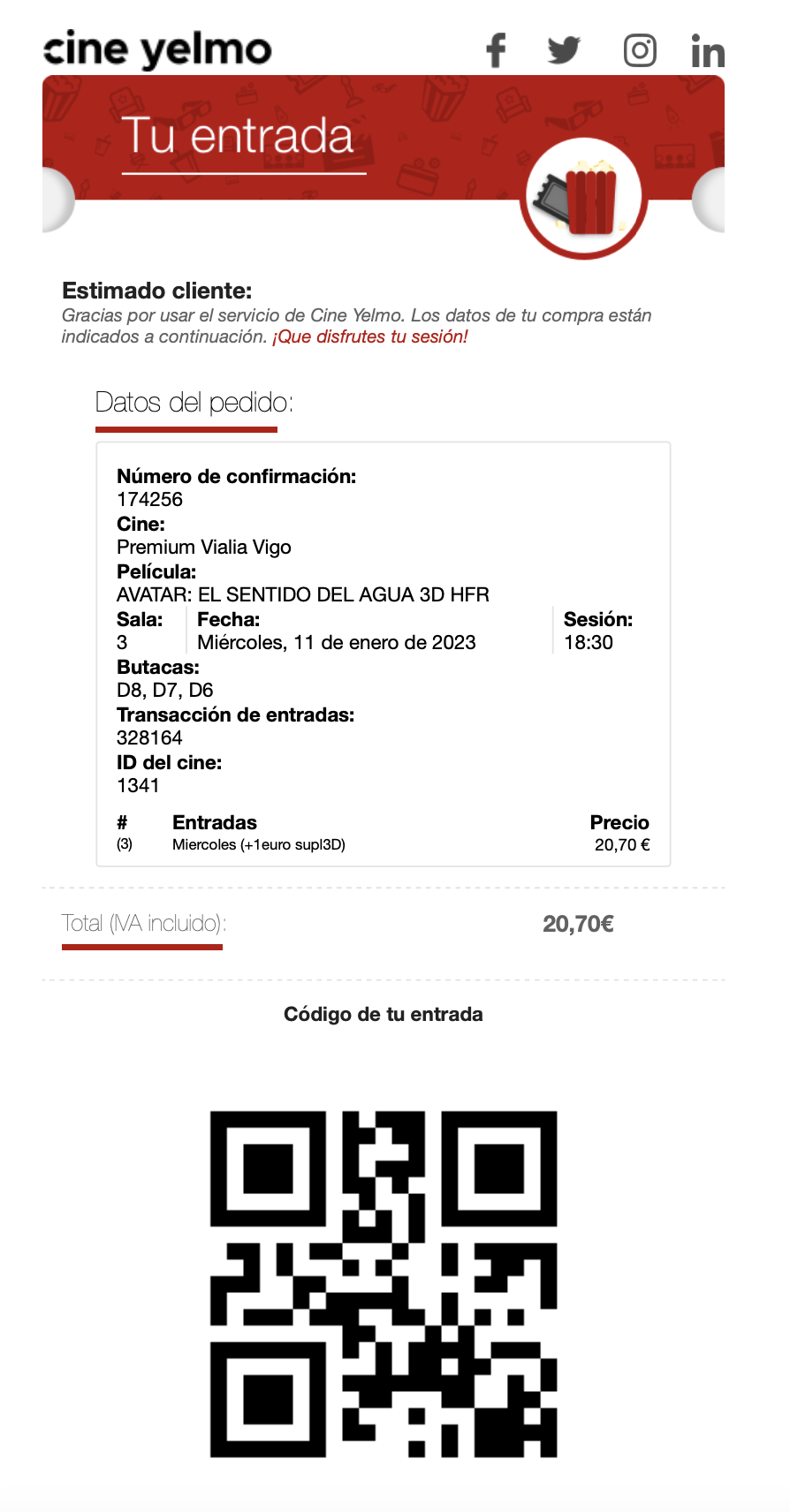

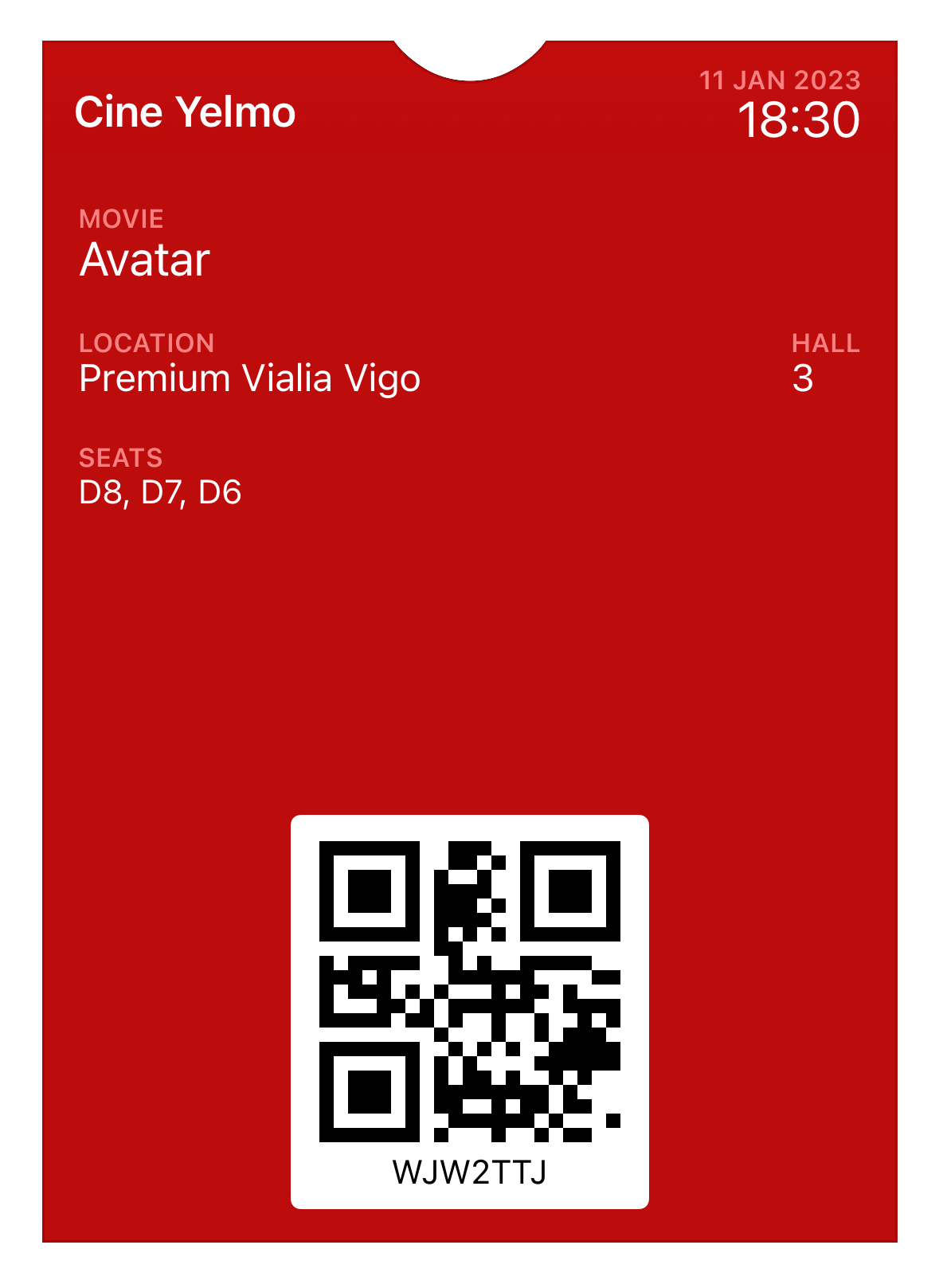

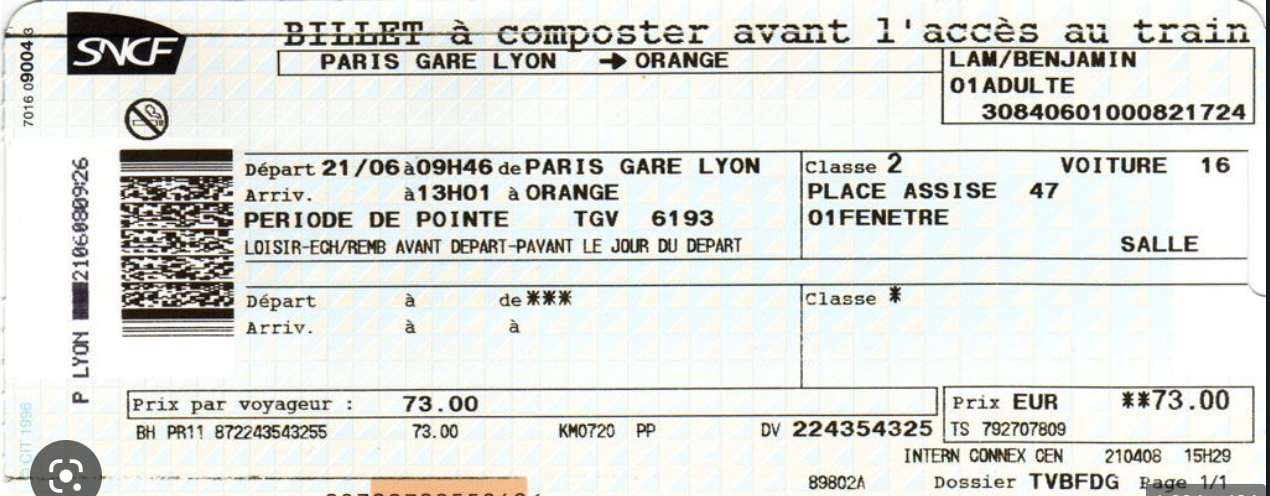

| Input | Pass |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MakePass

MakePass is available on the App Store for iPhone, iPad and Mac.